Interview with Miranda July

May 8, 2019

I first learned about filmmaker, artist, and writer Miranda July when Me and You and Everyone We Know was released. I don’t know if I saw the film because it was an art high school must-see or if it was because my older sister is close friends with Miranda’s friend Julia Bryan-Wilson. But, either way, I saw it and “pooping back and forth… forever” forever became a message passed [back and forth] between my good friends. Miranda has the remarkable ability to make work that is simultaneously sexy, dark, playful, awkward and sincere. We had a phone call to talk about trying to connection and missed connections.

Olivia de Salve Hi, lovely to meet you on the phone. I guess I’ll start asking you questions?

Miranda July Sounds good. Let’s jump right in.

OSV Okay so my first question: I had a teacher once tell me that the personal is often the most universal. Even though a lot of your work is fiction, the narratives feel very real and true because your work is filled with these moments that are so uniquely human. How do you think that there is truth in fiction? How do you use this as a tool to connect with your audience?

MJ Most everything I write comes out of some strong feeling that I’ve had. I’ve tried to just write straight, a lot closer to reality, but it just doesn’t take flight. There’s something missing. I can’t quite capture what it really felt like by sticking close to reality, so the real art of it to me is [in] loosening up, kind of letting go of the real story and letting another story come in that I feel free enough in and am having a good time in. At that point, some sort of alchemy happens where I think the feelings actually come across more precisely than if they had stayed [closer] to their original context.

But that little choice is always kind of a struggle. I often start out writing the real story, just to get the feelings down. Then later I mine that story for those details.

![]()

OSV That’s really interesting. Also in your work there are many ways of communicating. You use a lot of communication technologies, like AOL Instant Messenger and email, and your Somebody [mobile messaging] app. Do you think that these technologies facilitate communication or do you think they make it harder for people to connect?

MJ Well, you’ll notice that in my work, even when people are just talking, they’re not doing a very good job of communicating. And that’s interesting to me, and more revealing than if people were able to be therapists and precisely connect. So I think it’s kind of just the same thing. But in different technologies. I enjoy how that might play out. . . . You can do different things if it’s instant messaging because there are new and ridiculous ways that you might misunderstand each other.

In some ways, going back to your first question, maybe the most accurate way to connect isn’t through precision. Maybe there’s something about the clumsiness and the inarticulacy and the mistakes that actually creates something more human, like a more alive surface for two people to connect on. Even though reading the story, you have the sense of calamity, too. There is also something else like a ghost that comes out of that with its own kind of emotional truth. So yeah, but I definitely don’t think these tools are making us better. I think they’re just different venues, really, for the same mishaps.

![]()

![]()

![]()

OSV Going back to the awkward, how bad communicating can be more human, I think that’s actually because it’s more vulnerable. Then if it is more vulnerable, do these technologies maybe remove some of that vulnerability?

MJ That’s interesting. Yeah, maybe you’ve thought about that a little more. I think you’re right, but . . . it’s just like learning to read another language. I’m thinking of texting right now. It might be briefer, and people might be holding their cards in certain ways, but I think you can also learn. Like, if I were reading a story that involved a lot of texting, I think we all know that language well enough now that we’d be like, “I can see what’s happening here.” But it’s not in the words, because I’ve done that too. I’ve written that thing when I actually mean this thing. You know?

OSV Yeah.

MJ But I might be naïve in that. I don’t know if it’s just like not wanting to believe that something great is getting lost.

OSV Well, maybe it’s just like new kinds of miscommunication. So it’s vulnerable in its own way . . . human.

MJ Right, exactly.

OSV I have a question about the use of the body in your work. You’re present in a lot of the work that you make, and you’re an actor in all of your films, but you also did all this performance work. But even when you’re not in your work, a lot of your work engages with the viewer and prompts them to move through space. I’m thinking about your installation The Hallway [2008] and also your Somebody app. It’s true that the body is an essential tool for performance. Can you tell me about your relationship to bodies? Not necessarily just your own, but yours in relation to your audiences’?

![]()

MJ I am so in my head and I feel like [I’m] always refining what my brain can do. But it’s sort this surprise to also have a body, and [it] kind of feels like a freebie or something. Like, “Oh, I’ve not only come up with this more conceptual idea, but there’s this big, dumb, soft thing that people recognize.” It has a different kind of articulacy. Also, I am, at this point, sort of a trained writer, thinker, but on a physical level, I think I retain a real colloquial-ness. Let’s leave it that way. And something about that kind of amateurness is appealing to me, just even as an artist.

[The body] is an interesting material. Certainly in the present moment with performance, I feel like a lot of [people] can relate to me on that [level]. I might be doing something fairly complex, even say with the app. It’s a sort of complicated conceptual idea. But what it requires is to go do this thing with your dumb body. Go put it there. Something real basic and kind of doable. I like that simplicity. I also like objects in my work, simple objects, for the same reason that you can see them, they’re real, they’re grounded and that’s a nice counterpoint to a lot of the more sort of spiritual . . . feeling, you know?

OSV Yeah.

MJ Yeah. So it’s a relief to have a body in common with everyone.

OSV Because your work is a lot about connection or misconnection or awkwardness, I think it is really interesting when you actually do a performance because then you also have the added layer of a connection with the audience that you’re performing with.

MJ Yeah.

OSV Can you talk about a little bit how that dynamic plays into your work and how performance is different than working in other mediums, like film?

MJ Yeah, you’re right. When I’m writing something . . . I’m just sitting there alone. Like, it’s not really happening. I’m just remembering what connection is like or mis-connection. [When I’m] there with an audience . . . regardless of what I’m trying to do, there either is a connection happening or there isn’t in every moment. . . . It’s a very iterative thing, rehearsing and doing multiple shows, learning here’s where we’re open and free and able to connect, and here’s what I’m doing in this show that actually you would think would work but doesn’t. So it’s really like being in the lab or something all together. It’s like theories playing out in real time and a real demonstration of imperfection, you know?

Often I sort of just kind of build in, not failure, but the fact that, because it’s so often such a collaboration with the audience, I have to have thought of all those curveballs that can be thrown and allow for even the ones I haven’t thought of. That just keeps me so present. This is too reductive, but in some ways it’s like the fantasy of what writing is, like when you’re writing sometimes it feels quite wild. Like all this stuff is really happening, and you leave your computer in a daze. Like wow, that was a trip. But actually nothing happened. It was all in you, so [performance] is like that, but you come home after a show and it’s like that all really happened. Everyone was really there. We all saw it. There were witnesses. It’s wonderful for that reason.

![]()

OSV Does it change when you open up? Does it become more surprising when you open up control like in your “New Society” performance work [2015], how the audience is really involved in that performance?

[continue at the top of the page]

Miranda July Sounds good. Let’s jump right in.

OSV Okay so my first question: I had a teacher once tell me that the personal is often the most universal. Even though a lot of your work is fiction, the narratives feel very real and true because your work is filled with these moments that are so uniquely human. How do you think that there is truth in fiction? How do you use this as a tool to connect with your audience?

MJ Most everything I write comes out of some strong feeling that I’ve had. I’ve tried to just write straight, a lot closer to reality, but it just doesn’t take flight. There’s something missing. I can’t quite capture what it really felt like by sticking close to reality, so the real art of it to me is [in] loosening up, kind of letting go of the real story and letting another story come in that I feel free enough in and am having a good time in. At that point, some sort of alchemy happens where I think the feelings actually come across more precisely than if they had stayed [closer] to their original context.

But that little choice is always kind of a struggle. I often start out writing the real story, just to get the feelings down. Then later I mine that story for those details.

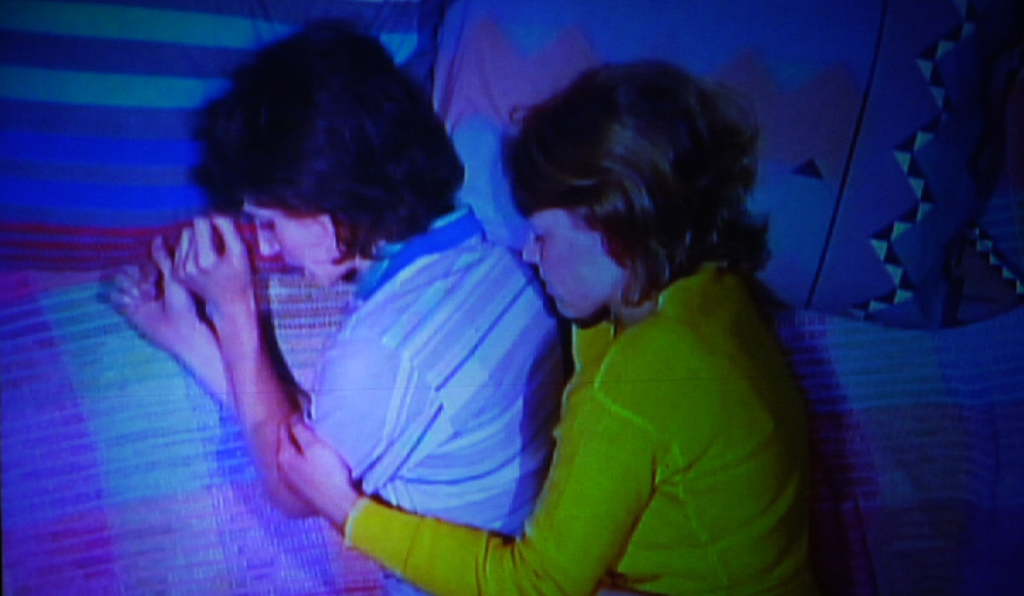

Miranda July, Still from Me and You and Everyone We Know, 2005

OSV That’s really interesting. Also in your work there are many ways of communicating. You use a lot of communication technologies, like AOL Instant Messenger and email, and your Somebody [mobile messaging] app. Do you think that these technologies facilitate communication or do you think they make it harder for people to connect?

MJ Well, you’ll notice that in my work, even when people are just talking, they’re not doing a very good job of communicating. And that’s interesting to me, and more revealing than if people were able to be therapists and precisely connect. So I think it’s kind of just the same thing. But in different technologies. I enjoy how that might play out. . . . You can do different things if it’s instant messaging because there are new and ridiculous ways that you might misunderstand each other.

In some ways, going back to your first question, maybe the most accurate way to connect isn’t through precision. Maybe there’s something about the clumsiness and the inarticulacy and the mistakes that actually creates something more human, like a more alive surface for two people to connect on. Even though reading the story, you have the sense of calamity, too. There is also something else like a ghost that comes out of that with its own kind of emotional truth. So yeah, but I definitely don’t think these tools are making us better. I think they’re just different venues, really, for the same mishaps.

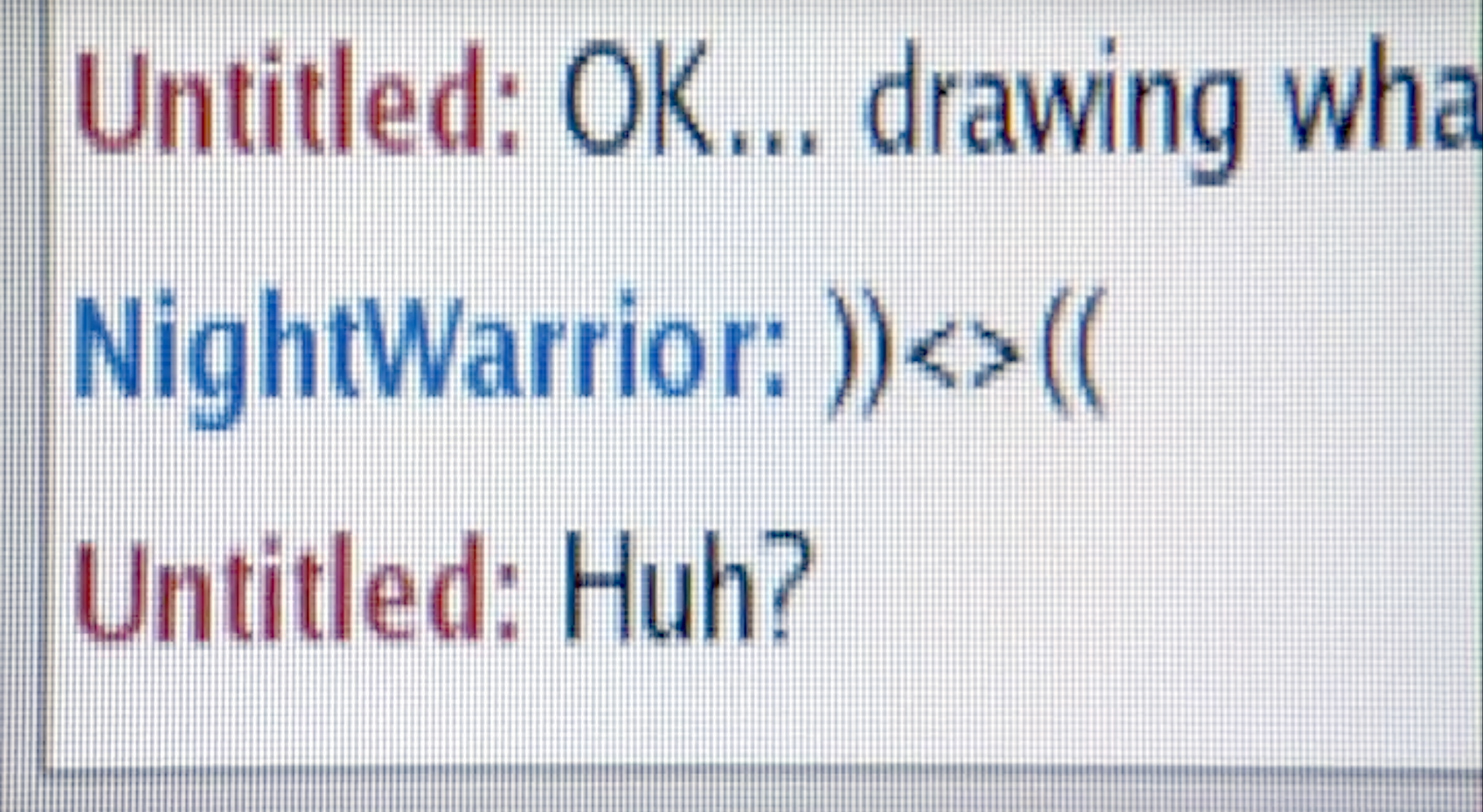

Miranda July, Still from Miu Miu Women’s Tales #8 – Somebody, 2014

OSV Going back to the awkward, how bad communicating can be more human, I think that’s actually because it’s more vulnerable. Then if it is more vulnerable, do these technologies maybe remove some of that vulnerability?

MJ That’s interesting. Yeah, maybe you’ve thought about that a little more. I think you’re right, but . . . it’s just like learning to read another language. I’m thinking of texting right now. It might be briefer, and people might be holding their cards in certain ways, but I think you can also learn. Like, if I were reading a story that involved a lot of texting, I think we all know that language well enough now that we’d be like, “I can see what’s happening here.” But it’s not in the words, because I’ve done that too. I’ve written that thing when I actually mean this thing. You know?

OSV Yeah.

MJ But I might be naïve in that. I don’t know if it’s just like not wanting to believe that something great is getting lost.

OSV Well, maybe it’s just like new kinds of miscommunication. So it’s vulnerable in its own way . . . human.

MJ Right, exactly.

OSV I have a question about the use of the body in your work. You’re present in a lot of the work that you make, and you’re an actor in all of your films, but you also did all this performance work. But even when you’re not in your work, a lot of your work engages with the viewer and prompts them to move through space. I’m thinking about your installation The Hallway [2008] and also your Somebody app. It’s true that the body is an essential tool for performance. Can you tell me about your relationship to bodies? Not necessarily just your own, but yours in relation to your audiences’?

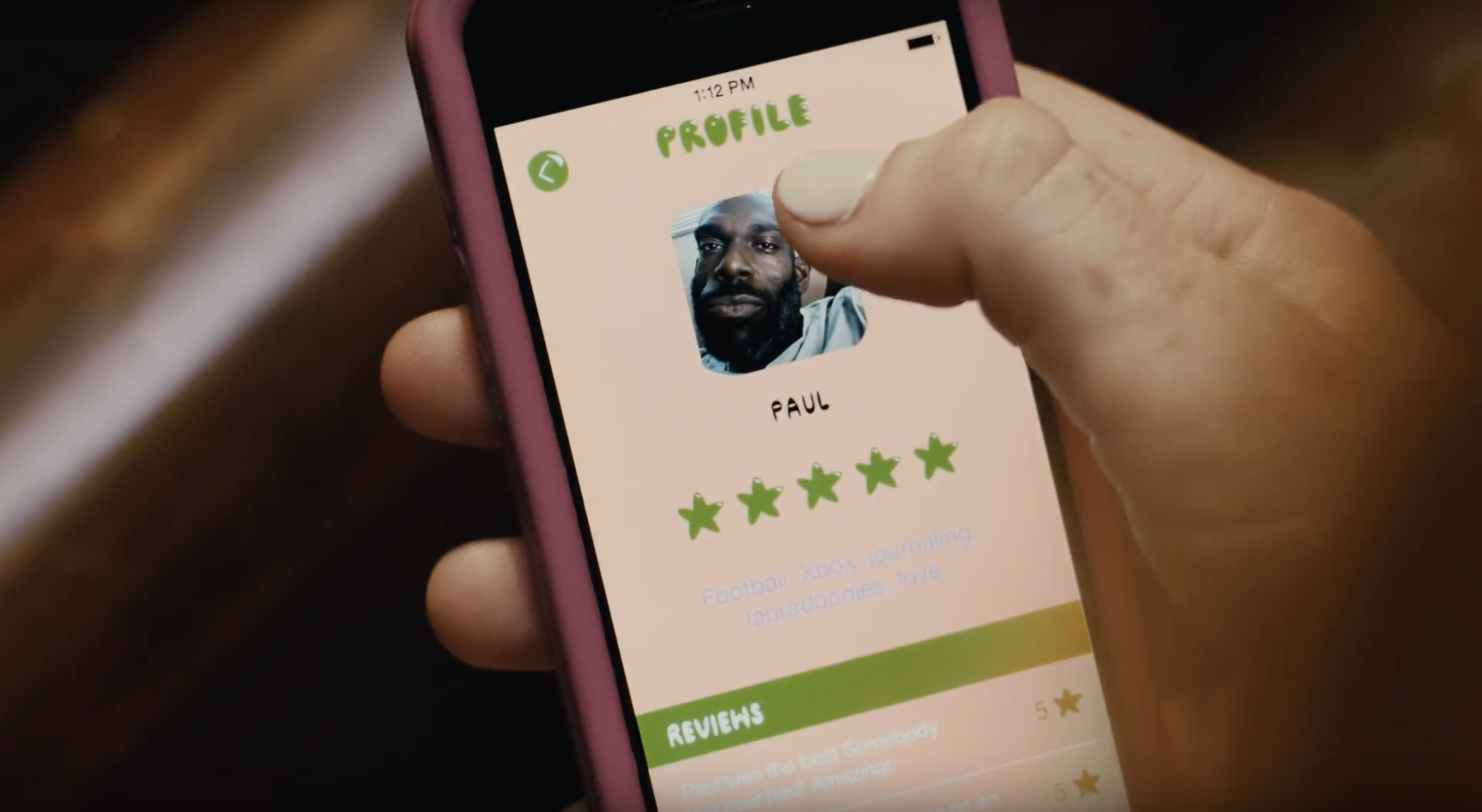

Miranda July, The Hallway, 2008

MJ I am so in my head and I feel like [I’m] always refining what my brain can do. But it’s sort this surprise to also have a body, and [it] kind of feels like a freebie or something. Like, “Oh, I’ve not only come up with this more conceptual idea, but there’s this big, dumb, soft thing that people recognize.” It has a different kind of articulacy. Also, I am, at this point, sort of a trained writer, thinker, but on a physical level, I think I retain a real colloquial-ness. Let’s leave it that way. And something about that kind of amateurness is appealing to me, just even as an artist.

[The body] is an interesting material. Certainly in the present moment with performance, I feel like a lot of [people] can relate to me on that [level]. I might be doing something fairly complex, even say with the app. It’s a sort of complicated conceptual idea. But what it requires is to go do this thing with your dumb body. Go put it there. Something real basic and kind of doable. I like that simplicity. I also like objects in my work, simple objects, for the same reason that you can see them, they’re real, they’re grounded and that’s a nice counterpoint to a lot of the more sort of spiritual . . . feeling, you know?

OSV Yeah.

MJ Yeah. So it’s a relief to have a body in common with everyone.

OSV Because your work is a lot about connection or misconnection or awkwardness, I think it is really interesting when you actually do a performance because then you also have the added layer of a connection with the audience that you’re performing with.

MJ Yeah.

OSV Can you talk about a little bit how that dynamic plays into your work and how performance is different than working in other mediums, like film?

MJ Yeah, you’re right. When I’m writing something . . . I’m just sitting there alone. Like, it’s not really happening. I’m just remembering what connection is like or mis-connection. [When I’m] there with an audience . . . regardless of what I’m trying to do, there either is a connection happening or there isn’t in every moment. . . . It’s a very iterative thing, rehearsing and doing multiple shows, learning here’s where we’re open and free and able to connect, and here’s what I’m doing in this show that actually you would think would work but doesn’t. So it’s really like being in the lab or something all together. It’s like theories playing out in real time and a real demonstration of imperfection, you know?

Often I sort of just kind of build in, not failure, but the fact that, because it’s so often such a collaboration with the audience, I have to have thought of all those curveballs that can be thrown and allow for even the ones I haven’t thought of. That just keeps me so present. This is too reductive, but in some ways it’s like the fantasy of what writing is, like when you’re writing sometimes it feels quite wild. Like all this stuff is really happening, and you leave your computer in a daze. Like wow, that was a trip. But actually nothing happened. It was all in you, so [performance] is like that, but you come home after a show and it’s like that all really happened. Everyone was really there. We all saw it. There were witnesses. It’s wonderful for that reason.

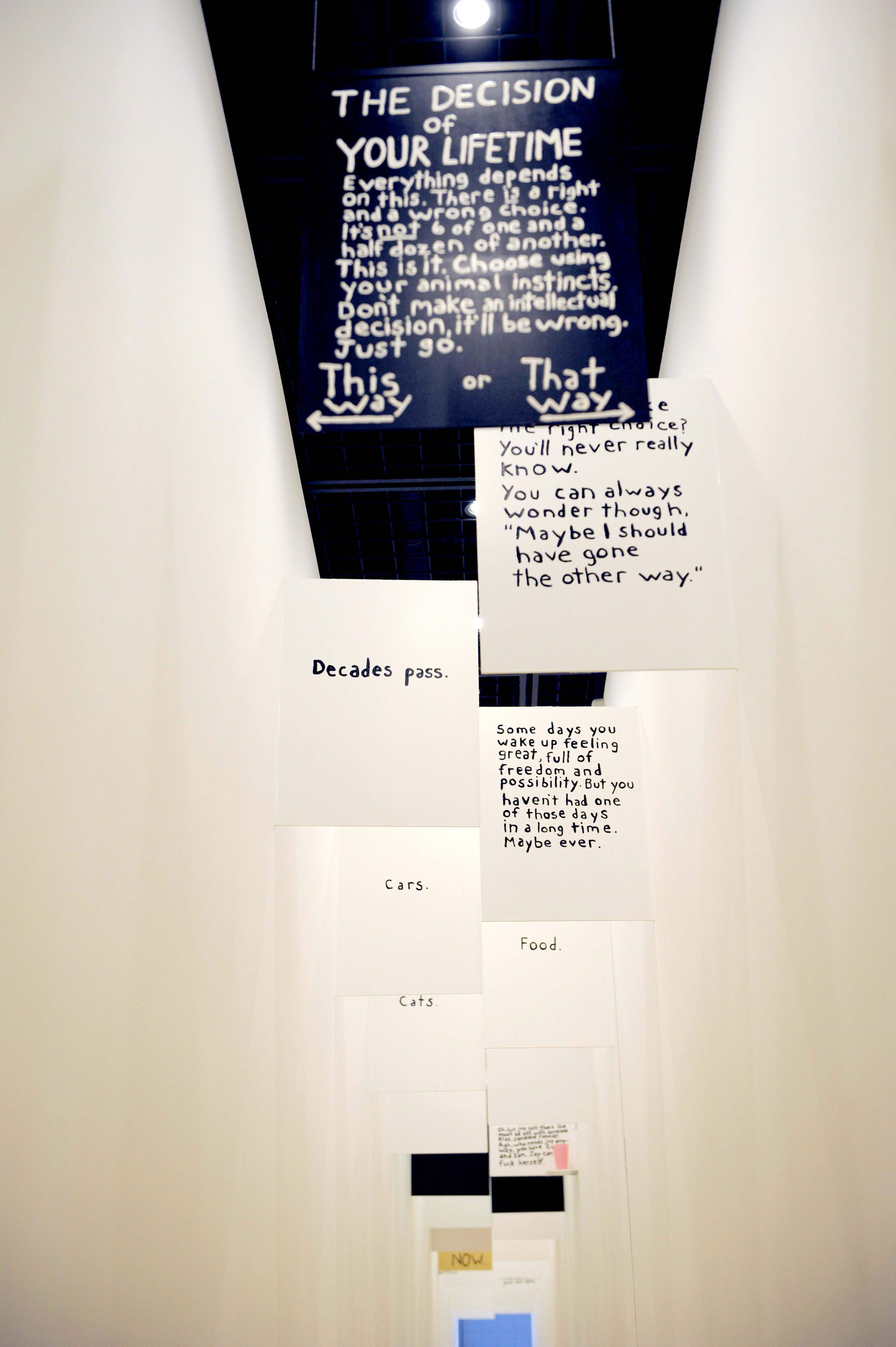

Miranda July, “New Society”, 2015

OSV Does it change when you open up? Does it become more surprising when you open up control like in your “New Society” performance work [2015], how the audience is really involved in that performance?

[continue at the top of the page]

MJ Yeah. It borders on impossible or intolerable. That show, it’s probably hard to see how much, even for the people in the audience, how much I really was doing this high-wire act and really didn’t know what was going to happen. I practiced it so much that I seemed to have this ease and control, but for me each night I didn’t know if it was going to work. I stopped doing that show with great relief. I never am going to do that again. I loved it, but it was terrifying. . . . I got less of that really fun feeling of just putting on a show, doing a great show for people . . . the good nights and bad nights were totally determined by how it played out with the audience. There were no bad nights, but I was at the edge of my seat. It was different.

OSV When you do other projects where people interact with your work, like 11 Heavy Things [ an artwork comprising eleven sculptures made for the 2009 Venice Biennale], are you surprised in the same way that you were in something that was more extreme, like “New Society,” or is it more expected maybe?

![]()

MJ Well, actually the first time, it’s not as high stakes. It’s a quieter little thing that’s playing out, but it is the same thing . . . people would pose with and stand on the objects. I labored to make them, and then they went on a boat all the way to Venice, and then it was kind of laborious installing them. Then the show opened, and I remember just sitting there in the grass with my husband trying to look fairly innocuous and invisible, and just as people entered the garden for the first time, I’m just holding my breath. It’s not like “New Society,” I can’t guide them to it. I just have to hope the work itself is enough of an invitation, and it was just such a joy to watch people do exactly that and take pictures of each other. I could have sat there all day, which isn’t how I . . . I don’t read my books or watch my movies. I don’t usually get to enjoy the work after it’s made like that. [It was bit similar to] the charity shop that I made [Interfaith Charity Shop at Selfridge’s, London, 2017]. I don’t know if you know about that. [I had] a little bit the same feeling watching it work, you know?

OSV I love that project so much. 11 Heavy Things looks joyful. Seeing the images of it and people interacting with it, it really does.

![]()

![]()

MJ Good. It’s funny looking at them now, it makes so much sense, but it was right before Instagram was invented, so I think it’s not just that it didn’t quite function as well as it might have with the internet. I think that kind of posing and taking pictures was a little bit more frowned upon then, you know? Whereas now . . .

OSV Oh, that’s so interesting. It’s a little uncomfortable at first, whereas now no one thinks twice.

MJ Yeah, now it’s like you’re clearly playing with something that already exists in the culture, but this was like, I know this exists. If you can give yourself up to it, you know it too. I think at the time it might’ve been perceived a little bit as—this is overstating it—but like a project that asks you to show off or something. You know what I mean? Maybe a little, it’d be easy to judge in that way.

OSV Yeah, totally. This is something I personally have been thinking a lot as being a grad student and making a bunch of work, but do you ever find that your work is contradictory, and can you tell me about that?

MJ What do you mean? What are you thinking of?

OSV Okay. A lot of the work that I make looks really modernist. I’m a graphic designer and I use a lot of primary colors, but a lot of the ideas I’m dealing with push against that, and it kind of deconstructs the structure that and then redefines it, if that makes sense.

MJ I relate to that so much. To some degree, for me, it’s not contradictory, it is just complex.

That is, two things, but both exist and can be together. But I do think there will always be a superficial read of something like that, which will be frustrating. I remember at one point complaining to a book editor, saying, I think people are equating my work with cupcakes, and The New Girl, the TV show. Nothing against Zooey Deschanel, but I’ve always had so much darkness in my work. I’m so surprised to be put in this category.

Of course, the people who are saying that don’t know the work or have only seen one thing. The editor said, “Look, a lot more people like cupcakes than like weird, dark, arty stuff.” It’s a fine problem to have, you know? It might feel like a judgment at times, but the truth is it’s goingto work in your favor, so you don’t need to worry about that.

There are other contradictions, I’m sure, in both our work.

OSV Yeah.

MJ Just trust in it, and the

right people will understand that interplay.

OSV Okay, cool. That’s smart. So, I have a random question about cats.

MJ Okay.

![]()

OSV This is kind of separate from a lot of the other questions that I’ve asked, but I was just really curious. Cats make a lot of appearances in your work, and they even take on roles in the films The Future [2011] and Madeline’s Madeline [2018]. I was wondering why they keep appearing, and also what it’s like to design a performance from a nonhuman perspective?

MJ I feel like it was just that one thing, which ended up being both a performance and a movie [The Future]. Madeline’s Madeline, of course, I didn’t write, so the cat stuff was just kind of a coincidence.

I mean, I had cats growing up. I like cats. In the case of The Future, it was a role-specific thing. One day, our dog ran off, pulled the leash away from us and ran after a stray cat. The cat ran into the street, and the cat got hit by a car, right then.

It all happened in an instant, and it was horrible. I was just starting to write what would be [the play] Things We Don’t Understand.

I had to deal with this cat and felt very responsible. It was a stray I had kind of known from the neighborhood. Meanwhile, a few months later, or weeks later, I was just desperately trying to figure out how to write. I felt so bad at it, and I always tell other people, well, just write from the feeling you have.

I’m like, okay, my feeling is that I don’t even know how to talk. I started writing in this odd voice of someone who couldn’t talk very well. It was sort of fun, it had a certain energy to it. It was very sad. I felt very sad and incapable, and kind of stray.

Gradually, as I wrote that voice I was like, who is this? Then, in some sort of guilty way, I was like, oh, it’s the cat that I was partly responsible for killing. Here it is. I just decided that was whose voice I was speaking in.

I just kept that thought, I never let it go. A lot of people suggested I let it go, it was not a good idea at all. So, that’s the specific story of how that cat ended up in the movie.

![]()

OSV That’s super interesting. I feel like that even ties back to the first question I asked, about the truth in—

MJ Yeah, yeah, exactly. Yeah.

OSV —which is cool. It’s great.

MJ Yeah.

OSV Okay, well I don’t want to take up too much of your time, because I know you’re super busy. This was super helpful.

MJ Well, thank you and good luck with it, and with everything.

OSV Thank you so, so much.

MJ Take care. Bye.

OSV When you do other projects where people interact with your work, like 11 Heavy Things [ an artwork comprising eleven sculptures made for the 2009 Venice Biennale], are you surprised in the same way that you were in something that was more extreme, like “New Society,” or is it more expected maybe?

Miranda July, 11 Heavy Things, 2009

MJ Well, actually the first time, it’s not as high stakes. It’s a quieter little thing that’s playing out, but it is the same thing . . . people would pose with and stand on the objects. I labored to make them, and then they went on a boat all the way to Venice, and then it was kind of laborious installing them. Then the show opened, and I remember just sitting there in the grass with my husband trying to look fairly innocuous and invisible, and just as people entered the garden for the first time, I’m just holding my breath. It’s not like “New Society,” I can’t guide them to it. I just have to hope the work itself is enough of an invitation, and it was just such a joy to watch people do exactly that and take pictures of each other. I could have sat there all day, which isn’t how I . . . I don’t read my books or watch my movies. I don’t usually get to enjoy the work after it’s made like that. [It was bit similar to] the charity shop that I made [Interfaith Charity Shop at Selfridge’s, London, 2017]. I don’t know if you know about that. [I had] a little bit the same feeling watching it work, you know?

OSV I love that project so much. 11 Heavy Things looks joyful. Seeing the images of it and people interacting with it, it really does.

Miranda July, Interfaith Charity Shop at Selfridge’s, London, 2017

MJ Good. It’s funny looking at them now, it makes so much sense, but it was right before Instagram was invented, so I think it’s not just that it didn’t quite function as well as it might have with the internet. I think that kind of posing and taking pictures was a little bit more frowned upon then, you know? Whereas now . . .

OSV Oh, that’s so interesting. It’s a little uncomfortable at first, whereas now no one thinks twice.

MJ Yeah, now it’s like you’re clearly playing with something that already exists in the culture, but this was like, I know this exists. If you can give yourself up to it, you know it too. I think at the time it might’ve been perceived a little bit as—this is overstating it—but like a project that asks you to show off or something. You know what I mean? Maybe a little, it’d be easy to judge in that way.

OSV Yeah, totally. This is something I personally have been thinking a lot as being a grad student and making a bunch of work, but do you ever find that your work is contradictory, and can you tell me about that?

MJ What do you mean? What are you thinking of?

OSV Okay. A lot of the work that I make looks really modernist. I’m a graphic designer and I use a lot of primary colors, but a lot of the ideas I’m dealing with push against that, and it kind of deconstructs the structure that and then redefines it, if that makes sense.

MJ I relate to that so much. To some degree, for me, it’s not contradictory, it is just complex.

That is, two things, but both exist and can be together. But I do think there will always be a superficial read of something like that, which will be frustrating. I remember at one point complaining to a book editor, saying, I think people are equating my work with cupcakes, and The New Girl, the TV show. Nothing against Zooey Deschanel, but I’ve always had so much darkness in my work. I’m so surprised to be put in this category.

Of course, the people who are saying that don’t know the work or have only seen one thing. The editor said, “Look, a lot more people like cupcakes than like weird, dark, arty stuff.” It’s a fine problem to have, you know? It might feel like a judgment at times, but the truth is it’s goingto work in your favor, so you don’t need to worry about that.

There are other contradictions, I’m sure, in both our work.

OSV Yeah.

MJ Just trust in it, and the

right people will understand that interplay.

OSV Okay, cool. That’s smart. So, I have a random question about cats.

MJ Okay.

Miranda July, The Future, 2011

OSV This is kind of separate from a lot of the other questions that I’ve asked, but I was just really curious. Cats make a lot of appearances in your work, and they even take on roles in the films The Future [2011] and Madeline’s Madeline [2018]. I was wondering why they keep appearing, and also what it’s like to design a performance from a nonhuman perspective?

MJ I feel like it was just that one thing, which ended up being both a performance and a movie [The Future]. Madeline’s Madeline, of course, I didn’t write, so the cat stuff was just kind of a coincidence.

I mean, I had cats growing up. I like cats. In the case of The Future, it was a role-specific thing. One day, our dog ran off, pulled the leash away from us and ran after a stray cat. The cat ran into the street, and the cat got hit by a car, right then.

It all happened in an instant, and it was horrible. I was just starting to write what would be [the play] Things We Don’t Understand.

I had to deal with this cat and felt very responsible. It was a stray I had kind of known from the neighborhood. Meanwhile, a few months later, or weeks later, I was just desperately trying to figure out how to write. I felt so bad at it, and I always tell other people, well, just write from the feeling you have.

I’m like, okay, my feeling is that I don’t even know how to talk. I started writing in this odd voice of someone who couldn’t talk very well. It was sort of fun, it had a certain energy to it. It was very sad. I felt very sad and incapable, and kind of stray.

Gradually, as I wrote that voice I was like, who is this? Then, in some sort of guilty way, I was like, oh, it’s the cat that I was partly responsible for killing. Here it is. I just decided that was whose voice I was speaking in.

I just kept that thought, I never let it go. A lot of people suggested I let it go, it was not a good idea at all. So, that’s the specific story of how that cat ended up in the movie.

Miranda July, Things We Don’t Understand, 2006

OSV That’s super interesting. I feel like that even ties back to the first question I asked, about the truth in—

MJ Yeah, yeah, exactly. Yeah.

OSV —which is cool. It’s great.

MJ Yeah.

OSV Okay, well I don’t want to take up too much of your time, because I know you’re super busy. This was super helpful.

MJ Well, thank you and good luck with it, and with everything.

OSV Thank you so, so much.

MJ Take care. Bye.